The John Locke Project

May 30, 2021

Anyone who regularly follows recent events would have to admit that democracy is in a rather terrible state these days, though it seems that only a meager few are willing to exert any force to rescue it. Democracy’s triumph over fascism and later communism has become a distant memory, while the rise of authoritarian China and Russia offers today’s democracies little remove from the possibility that their system of government may be run over. The outlook is even bleaker on the home front, where a steady diet of lies and a dull wariness of the status quo has launched the careers of many populist candidates who bristle at the mere suggestion of protecting democratic institutions.

Democracy’s doldrums in the 21st century have prompted, somewhat understandably, a critical reexamination of the concept. In a time when elected representatives lie about the security of elections or incite mobs to assault national legislatures, evoking the revolutionary image of the people storming the palace and throwing the elites off balustrades, it’s awfully natural to wonder what good democracy is in the first place. Is democracy, one might ask, just a joust between foes, a war between irreconcilable factions where the ballot box is the battlefield? Is democracy just a great tug of war between Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, urban dwellers and country folk?

Such views of democracy as electoralism is essentialist and wrong, of course, but it is a natural consequence of today’s political environment. A more macro view of trends makes it clear that democracy is receding from all four corners of the globe, from the Philippines to Hungary to Venezuela. Ever more increasingly democracy is viewed as the object of Western Europeans and North Americans rather than the right of all people. But even the inhabitants of the democratic world are displeased with their own system of government, which has devolved into electoralism. In the West, more people than ever, particularly young people, are desirous of substantial revisions to the makeup of their governments. For too many, democracy has lost its way.

If democracy has been receding around the world, and if democracy has been essentialized beyond recognition into electoralism, it would then be appropriate to interrogate the essential question: What is democracy?

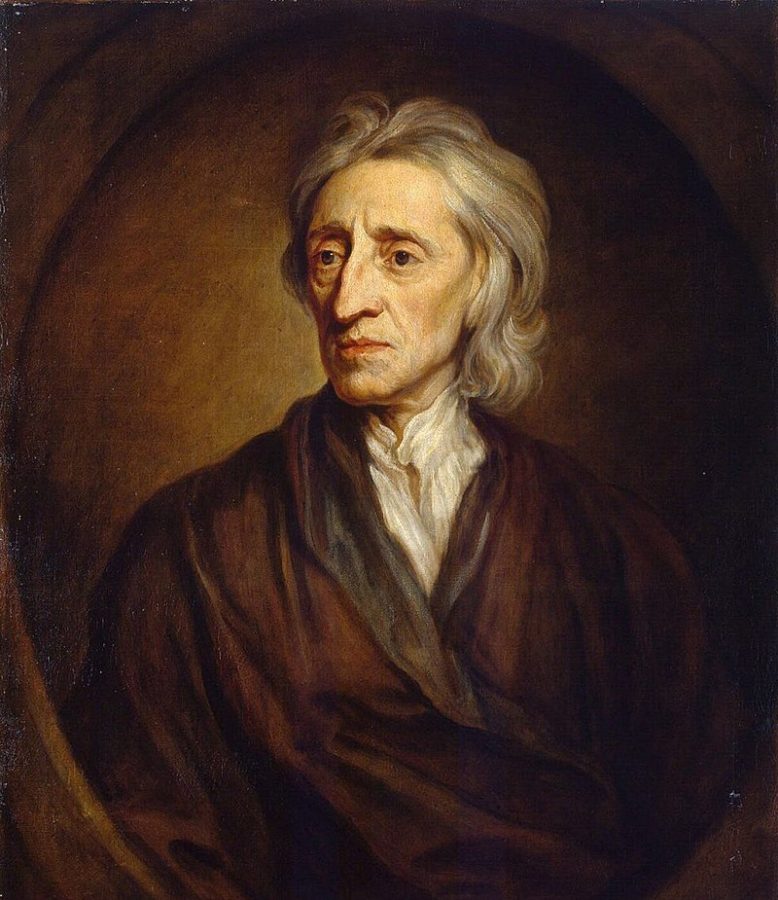

Enter John Locke.

John Locke, an English philosopher of the 17th century, is most famous for his Two Treatises of Government, the first articulation of modern democratic theory. Although previous thinkers articulated many of the principles enshrined in the American political system, it is to John Locke that the country owes the bedrock foundation of its democratic principles.

Locke’s England was submersed in religious and political conflict. He grew into adulthood during the English Civil War, during the victorious forces of Oliver Cromwell apprehended and beheaded English King Charles I, an act without any precedent in the nation’s history. Cromwell would later rule Britain as its Lord Protector, though after his death the late king’s son, Charles II, swiftly retook the throne. Later in Locke’s life, James II, a Catholic, suffered a coup d’état and was replaced by Protestants William III and Mary II.

Through the great upheaval England saw the birth of new ideas that questioned the function and nature of government. Some thinkers, like Thomas Hobbes, believed that humans were unfit to direct their own lives and should surrender their rights to an absolute power, a government whose authority over its people was near limitless. Locke disagreed. He reasoned that governments ought to always remain limited in the scope of their abilities, obliged to extend their powers only for the protection of its citizens’ rights to life, liberty and property. For Locke, any legitimate government must rely on the consent of the governed, its citizens, as the source of political power. Contrary to older schools of thinking, which held that a government’s right to rule stemmed from God’s mandate, Locke argued that ultimate authority rested with the people who, if they were dissatisfied with their leaders, had the moral prerogative to overthrow the government and constitute a new one.

Locke’s ideas were revolutionary, and they motivated many of the leaders that led America’s ragtag rebellion against British rule. Thomas Jefferson was greatly inspired by Locke, and echoes of John Locke’s three fundamental natural rights — life, liberty and property — can be heard in the Declaration of Independence’s “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The Founding Fathers paid close attention to Locke when they drafted the Constitution.

But Locke’s influence extends far beyond the United States. The core tenets of his political theory—that all men are created equal, possessing certain natural rights that transcend governments, and that governments exist to serve the people and must be by nature limited—have been incorporated into the governing philosophies of every single democracy on Earth, from Sweden to India. No person is more singularly responsible for the development of modern democracy as Locke.

The John Locke Project is the project of democracy, how to maintain it and how to preserve it against threats. The Project has been neglected by politicians and largely forgotten by the people, more or less because the people have become so habituated to democracy that they cannot understand what it may be like to live without it. The preeminence of the liberal democratic order has made us lazy in our habits, too secure in our beliefs that, yes, democracy is right and yes, that the arch of human history bends towards progress without persistent human intervention.

Neglect for democratic institutions is a chronic problem in American politics, but it is not without remedy. In order to reinvigorate the public’s trust in democracy, civic leaders must return to the fundamental values around which America’s forebears constructed the nation’s democracy. Democratic values of equality, individual liberty, rule of law, secularism, and freedom of speech, religion, and thought must be extolled in classrooms, and the founding texts of democracy, among them the Two Treatises, must be transmitted to students. Schools do too little to teach proper civic values to their students. This is a mistake, one whose price this country has been made to pay during the past four decades.

If all of John Locke’s philosophy were to be condensed down to a single sentence that would encapsulate his most essential message, it would be this: We must be willing and active participants in the forces that govern our lives. Democracy can never be a spectator sport. Its preservation relies on the people’s willingness to act, to give consent to their governors or, if necessary, to withhold it, but never to become passive, complicit or disinterested. Apathy leads men down the way of slavery.

Think of democracy like a defense wall surrounding a city. The fortification itself, the stone edifice, is sturdy enough to defend against invaders for a while, but it cannot stand alone, more so in the face of relentless attacks that, as time beats on, diminish its protective qualities. The city wall needs sentinels in the tower, soldiers ready to fend off invaders with sword or bow in hand. The wall needs skilled artisans, stone masons, engineers, and bricklayers who, whenever the wall requires it, will remove old, decrepit sections of the wall and replace them with newer, steelier components. But most importantly, the wall requires the trust of the city folk who reside within it. Because if the citizens believe that the wall will no longer protect them, or if they become so apathetic as to consider that their way of life is itself unworthy of defense, then all hope is lost. The people may as well tear down the walls themselves, draw up the portcullis and welcome their invaders with outstretched arms.

For all but a select few, the consequences of living in an undemocratic world are intensely terrible. Americans often look with pity on activists in Russia, China, Belarus, or Saudi Arabia who suffer extraordinary oppression at the hands of dictatorial regimes. Or we may think of the recent coup d’état in Myanmar, during which that nation’s police and armed forces butchered rows of peaceful protestors or loosed canines on innocent women and children. For Americans, political repression in the third world is a clear warning. All governments are disposed to tyranny, the American government no less. Without a radical rediscovery of the values and norms John Locke gifted our forefathers over three centuries ago, democracy here and around the world is doomed, possibly forever.